Since late 2019 I have been working with the IQM Quantum Computers team as an advisor. IQM is an archetype of a deep tech company where most of the team have research background and they are addressing a new market. Couple of weeks ago we published a paper on our suggestions of what should be done by the European Union (EU) to encourage the quantum computing industry in Europe. Here are some of my personal thoughts about the topic of the paper.

There has been some discussion lately that the EU venture capital scene is somehow broken, or that the EU Commission’s own accelerator and funding arm, the EIC accelerator is bad for the whole European venture capital ecosystem. Such discussion is mainly fuelled by individuals who think that the EU Commission’s or individual nation states’ participation in the venture capital industry somehow affects the whole industry negatively. Apparently, some think that too much capital is a bad thing or that somehow governmental venture capital is not focused on returns. I wonder, why is more capital a bad thing really? If you have a superior product then competition is good for you.

Setting aside the discussions over too much money or who should be participating in venture capital, what then should the EU Commission’s or the nation states’ role be in something like quantum computing?

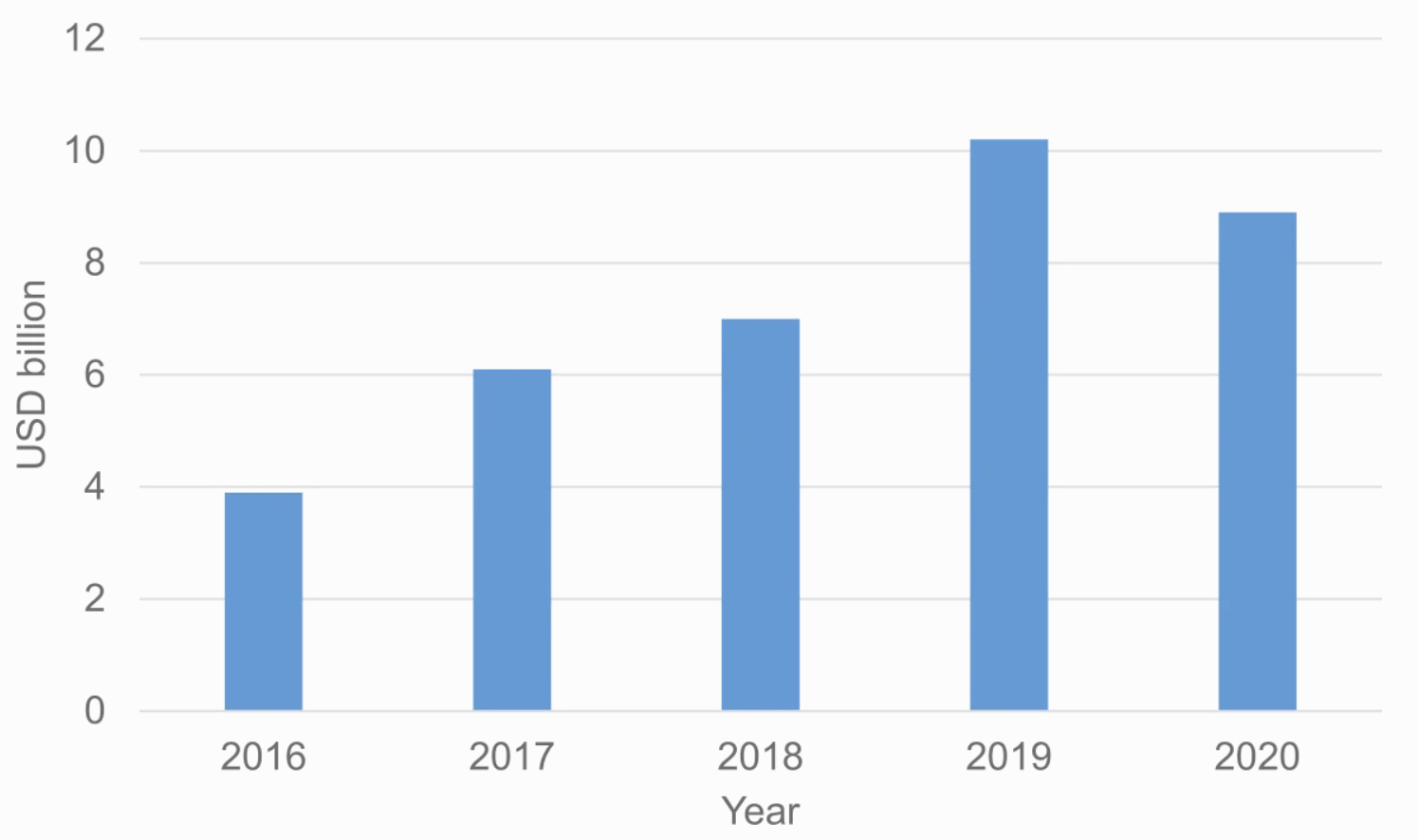

Capital invested in European deep-technology companies in each year. The data for 2020 are normalized for the full year based on data until September 2020. Source. Data provided by Atomico in: Atomico, State of European Tech 2020.

A school of thought exists where governments should focus on so-called funding gaps or market failures, where something is so risky or so new that private money cannot or does not want to invest into the field yet. To get that technology forward or to establish that industry, governments should act as the first investors or buyers. I am personally part of that school of thought. Historically, this role has been played by especially the militaries of different countries. For example, the United States has DARPA, which funds many immature technologies with future promise. Even though lately there has been some startup industry drama around the topic, I do not think that many resist the role of governments directly helping basic research and the commercialization of technology. Resistance, if any, concerns the role of the government and politicians with the technology industry.

I have adopted the following position: scientists discover, businesses commercialize, markets decide, and politicians support.

When politicians start to pick technologies and go into the specifics, problems may arise. Putting this all into the quantum computing context, the field has much future promise. Now, due to the quite long period of low interest rates globally, more money than ever has flowed into deep tech startups. While it looks like that the period of low interest rates is slowly coming to an end, it is likely that unless the interest rates raise quite rapidly, there will be private money available for deep tech projects such as quantum computing in the coming years also.

The role of deep tech companies should not be understated. Some, like Martin Krupp, paint deep tech as a force for change in the world: “Many deeptech startups aim to do more than make money, they apply scientific research to solve fundamental problems and create value for society.” This is due to the basic research origins, where the researchers want to address a problem that exists with new technology. As that technology gets commercialized it finds many application areas, but generally the first companies – just as with quantum computing – are looking to solve the big problems in order to raise enough interest and funding.

Why then should the EU commission and the member states participate in funding something like quantum computing, where there seems to be private money available? There are couple of reasons. While my opinion is that EU area never had an issue with not having money available for investment, there just is not enough money with the tolerance for extremely risky projects like quantum computing. Scaling the technology and a company such as IQM requires large amounts of capital. Secondly, we certainly need to monetize more of the excellent science we do within the EU. Marie Mawad has written about the topic lately. The better we monetize what we do, the more we can afford to do basic research. Thirdly, the EU should have its own technology ecosystem. Technology these days means influence and if we do not have our own strength in it, we will no doubt suffer the consequences.

While we discuss quantum computing in our paper, it could have been written about many other areas of science. Commercialization is an area where the EU and its member states are behind countries such as the United States. This is one of the main issues we need to fix in order to make our research more efficient. The less we are able to effectively commercialize our own innovation, the more we just pay the bills for other countries and areas to commercialize that same research by hiring the talent.

Do the EU and its member states then have a chance with quantum computing? Certainly. The world today is forming more and more into three blocks: the EU, USA and China. As we discuss in the paper, the EU academia is extremely strong globally. The thing we lack is the big technology companies that can fund the research for years to come. Interest rates do not stay low forever, trends change, focuses change. If the EU wants to be strong in quantum computing, it needs to take a strategic view of supporting the industry until it will be able to stand on its own.